Your life in a few lines, since the start

Actually I became a journalist by accident because I didn’t know what to do and what I wanted to study. In the beginning I wanted to do filmmaking but my parents were opposed to this saying I’ll end up homeless on the street! So I ended up in business school in order to get a degree and get out.

One of the marketing courses at the university was taught by a very inspiring teacher and once she told me (judging a paper part of a project): ‘Ibrahim you’re a very good writer!’. It never occurred to me that I could write but that experience somehow put me completely on another path: one, I realized that I could actually write; two, it ended up by me be put in touch with a publication. And I started writing for them when I was studying; I also started soon to write for other publications too, so I became a journalist.

As a child, I grew up in a small village close to the sea in the North of Lebanon, next to Tripoli. When I turned eighteen I went to Beirut to study. My parents were in Saudi and when they came back to Lebanon the war got so crazy that they moved to the countryside.

I did like this journalism work for a bit, then I worked in advertising for a bit and then, when the energy of Arab Spring became to bubble, I felt that that working with these publications can become very disrespectful to the readers’ intelligence – some magazines receive press releases by companies and publish them intact without any critique.

I felt also there was the lack of a platform could catch the energy of this world, of young Arab people in order to let them understand where they’re going.

When you talk of Arab world, there is always a single narrative that says it’s a devastated region torn by war where opportunities are lacking.

I wanted to stand for a more hopeful narrative, that’s how the idea of The Outpost was born and this is why it has been called the magazine of possibilities.

We launched the first issue in September 2012 (six years ago) and was very much an experiment, as much of my projects: we called that very first issue 0 and waited to see which the response could be. It was very positive and so we tried another issue and another one. They were all experiments because we did not have a publishing model. In the beginning we tried to find advertisers who did not come so we crowd-fund it and then get grants from institutions to go on.

Is that possible in Lebanon or are you forced to go in other countries?

There are funds like the Arab Fund for Art and Culture and others, which I never received grants from (but I published two books for them), I got a sustain from organizations in Amsterdam like the Prince Claus Fund. We did make profits with publishing and we reversed them on the magazine.

Prince Claus Fund seems very active in Lebanon, we recently interviewed a Syrian director who shot in Lebanon and whose film (premiered and awarded at Venice Film Festival) was supported by a grant of the same organization.

They do a lot in cinema, indeed!

Are there other magazines which obtain grants maybe because they’re more grateful with actual powers in Lebanon? To put it in a different way: is there any choice to still publish magazines which are less comfortable with the political power in the country?

In Lebanon the media landscape is very much controlled. Powerful media companies and other sources of informations are part of the system when is not directly the government to publish via a very restricted system of licenses to broadcast or publish (owned by politicians from where you have to buy them in order to establish a new media).

When I went to the media agencies to ask to search advertising for The Outpost, a women who worked there told me ‘If I want to sell your magazine I need a guide to explain my clients what your magazine is about’.

They’re used to this kind of easy and cheap journalism and they wouldn’t expect someone walking in a store and buy such a quality magazine. I am talking of course of mainstream media agencies.

I always had a problem to access the needed money but this was not preventing me to found my own magazine. Of course the system is not made for people like me who want to present a new voice.

I wish to return to the meaning of the title of The Outpost: it can be a place where to defend yourself or from where to attack.

Yes but there is also ‘a magazine of possibilities’ which mean that they could happen sooner or later.

Our name is quite a story!

We began to design the magazine, to detail the distribution and to collect stories and so on but suddenly reckoned we did not have a name yet for the publication even if we were expected to print it very soon!

Then, Raafat (my best friend and the creative director at that time) and I met in the football field of a university campus: it was cloudy, it looked post-apocalyptic!

We urged ourselves to find a name and he was asking me if I have listened this song by Friendly Fires, called Paris which according to him was saying also ‘we’re watching the stars from the outpost’.

I told him that ‘outpost’ was a very good name, perfect!

We’re so excited that when I went home I googled the lyric but did not find any outpost in the words….it was indeed saying ‘we’re watching the stars that were out for us’ but he understood outpost and so we had the name!

Your language since the beginning was English, this because you wanted to be read abroad also…and to export your vision of the Arab world elsewhere but it could be also made for the expats living there.

This question reminded me of a thought that I lost before when replying to a previous question! Publishing in English enables you to do so much compared to what is published in Arabic because the government thinks that something in English and French is not a threat to the public opinion in our country and they let you do something. These educated people who can consume their media in English and French are irrelevant in terms of figures for the controllers and cannot massively influence others.

The choice to publish in English was very natural for all of us, because we attended American schools as kids (the choice in our country is English or French, even in public schools). It felt a natural thing to do and we wanted to appeal people like us but also to reach an international audience to break the stereotypes about the Region.

After a few years of publishing I felt the limitation of a magazine published in English. If we wanted to create changes in our country, and not abroad, we had to change.

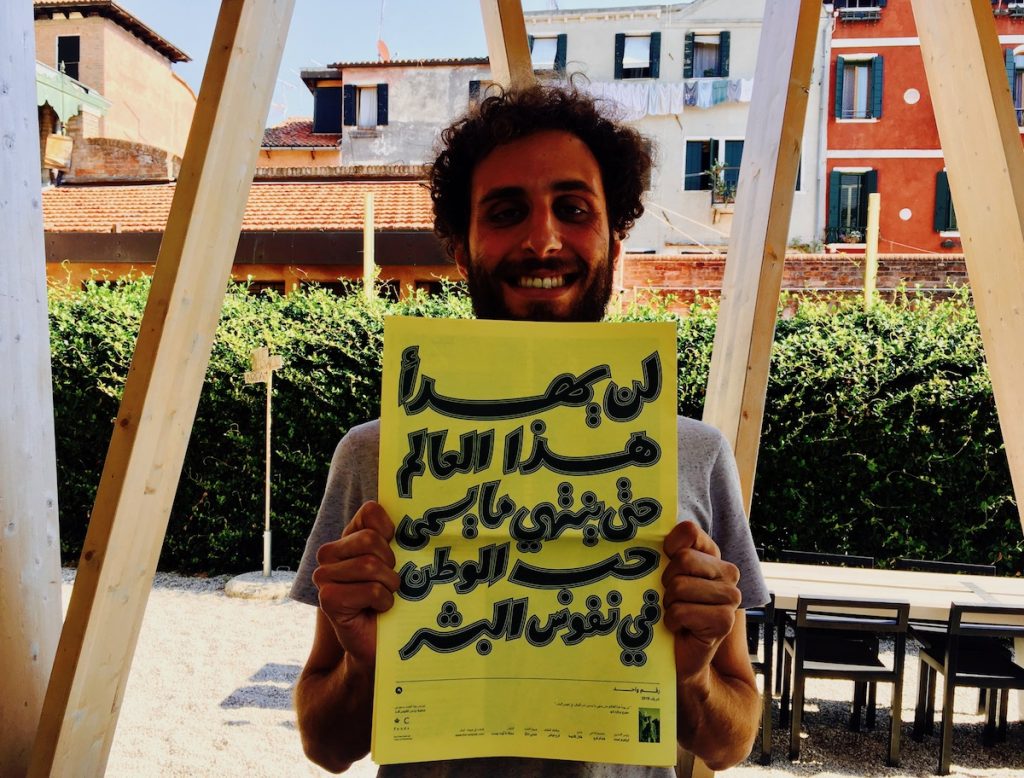

On the very last issue we published we decided to have an entirely Arabic version. The choice was also to give away for free that version.

The last publication was on the issue of ‘home’.

The magazine was always having three sections as follows:

What’s happening

What’s is not happening

What could it happen

Within those three sections we always played with contents around a theme, the last as said was ‘home’ (the possibility of finding home).

When we started to think to the Arabic version of that issue, in Arabic we have at least ten words to translate home. So we asked to a bunch of writers how they would translate ‘home’ in Arabic. And they came all with different definitions which have been used by each of them to build their stories.

Were those writers all Arabs but of different places?

Yes. Religious or not religious. One maybe touched spirituality but our issue was mostly about geography or politics. A lot of them has been touched by being refugee, like people in Palestine, Algeria or Syria. For instance there was a very good piece tracing the history of Algeria.

Why the yellow color of the ‘home’ issue?

Any issue was having a different color, the last was yellow. We used only two colors because it was cheaper in printing budgets.

Can readers write letter to your magazine? Is there any specific one you want to recall for us?

Yes, they were having the option to write us, I have a few letters and incidents in my memory. When we started to publish, I received this Facebook message for a lady called Shereen from Cairo and she was telling us how she was so inspired from us that she decided to start her own literary publication in Cairo. That was the very first message we got! It was really like wooow!

You can see how much writing and publishing can positively influence others.

Once I was in Berlin, somebody put me in touch with a Lebanese filmmaker who was living there. He picked up randomly the magazine in a cafe in Berlin, really randomly. He did not know anything about the publication and posted something on FB, a friend read it and sent it to me.

So we met and he was liking so much the ‘body’ issue (which came before the ‘home’ issue) that he decided to call an organs donations centre in Beirut and donate his organs.

I started again to think to the impact a publication can have (at a minimal level if we take in consideration mine which is not mainstream) and I projected that impact if thinking about the reach of mainstream media (not only in print and online). Especially in Arabic.

Two years ago, especially for these considerations and to have a new vision and how to get there, we stopped publishing The Outpost and tried to look inside us to face this crucial element.

You’re so thinking to a new model right now. Do you still have faith in paper?

Yes. I still have a faith in paper and did not think the magazine would have reached its position if only online or in a different format. Paper gives a value other medias don’t give especially in these times when news is often trash.

What about a digital version of the printed ones in order to cut costs and be always published?

Many people asked us the same. The simple reason is the pdfs were made for a reading experience, to be put online would request a total redesign for an online fruition. This costed money which we did not have at the moment.

I have lots of ideas to continue the experience of The Outpost and still don’t know where this process may lead me. In June we launched an online radio, we had very positive feedback and podcasting now is becoming a big thing.

I felt that radio is a space we can let happen with lots of things happening around at the same time. We ended up also to have writing workshops with underprivileged children. They came and we did four workshop with them in Beirut (to write bedtime stories). They’re never being put in a space where to expand their imagination and being creative before and, for instance, a radio is perfect for these purposes without mentioning to read stories!

A radio is also very cheap! We wanted to investigate also how to build a 24h/7 palimpsest by involving entire communities in Beirut. We looked for grants to realize it but even if they did not came, we succeeded to realize it by ourselves.

I am based in Beirut and make more and a lot of sense there, not in Berlin where the magazine was just printed and distributed (because it was cheaper and because the biggest chunk of readers was in Europe not in Middle East).

What about the scene for lifestyle magazine in Beirut?

There is a scene, a lot! People keep on asking me to bring back The Outpost. There is a huge demand because Beirut is a cosmopolitan city. My friend Jade publishes a food magazine which tries to depict the identity of the country through food. She is also opening a shop selling not only the magazine but its little universe. She is going also to open a bed&breakfast, I think this is the path – to create an ecosystem around the publication to make it financially more consistent. To capture the readers on the ground, also.

What about the events (or a bar) as a strategy to fundraise magazine?

I experimented them in the radio version. And regarding the bar, that’s a very good idea in Beirut!

I wanted to do something with poetry, I don’t know yet what. In Kenya I was working with an Italian NGO and troubled kids who were perfect poets.

If you want to influence public opinion – and at these times we’re really in the need of a big shift in our consciousness, the planet is exploding and many are the most urgent issues – the easiest way can be in form of songs, or poetry. This could be the key of success.

Which is a favorite or a special place, or a secret place, where do you go often to chill out, to read in peace or to get recharged in Beirut?

I go to the American University where I graduated, it’s very close to my house and I think it has one of the most gorgeous campuses I have ever visited, at least among the ones I know!

It’s all packed in one place and is like a park. It’s beside the biggest park in Beirut which once was closed and now is open with a huge bunch of regulations.

I already imagine what you gifted to your adopted city, Beirut, with your magazine but I don’t imagine what Beirut gifted or gave back to you?

It gave me the space to experiment with all this, it allowed me to do so and I grew up as a different person thanks to it.

A talent you have, the one you miss

Even when I was publishing the magazine and writing for other publications apart mine, I was never considering me as a writer. I was always feeling as an impostor anyway: now I feel I am a writer and have developed a skill. I also recently discovered I can write poetry in Arabic and in English. And I feel I want to do something with music (in Berlin I was attending music workshops with softwares, I want to come back to that). I feel also singing helps a lot into improving your communications skills and I want to practice it.

Any favorite food and drink?

I love Arak which is our version of an anise drink.

I love to drink it accompanied with our versions of ‘tapas’, called mezze, a perfect combination!

The music and the book with you in these days?

I’m reading a book called Alif the Unseen by G. Willow Wilson which my friend collaborator – who is American with Indian origins – gave it to me last time she was in Beirut, it’s fiction and did not read it since longtime (I left it in Beirut). It’s the story of a programmer settled in Middle East.

Now I’m very much into electronic music in order to be able to make this music by myself. When you see dance-floors you can easily think it’s a model of interaction for our future.

Where do you see yourself in ten years from now given you’re still very young, just 32 years old…

I don’t know. Maybe still in the Middle East, by using Beirut as base to travel a lot, which is something I love to do.

I would love to write a book and in maybe in ten years I would have accomplished and published it.

Maybe in ten years I would have sorted my ideal multimedia form to publish again The Outpost, it’s just a question of time about how, where and why.

Is there something special you’ve learned from life so far? This questions is normally the most difficult for any of our interviewed people of this world…

We always say – as part of this culture – that the more efforts you put in something the higher will be the places you’re gonna reach.

I feel that this culture really glorifies the struggle. We have to struggle, to put so much pain and hardship effort to do something!

I actually realized the opposite: the more effortless and joyful and enjoyable the process is the better the result will be. And I have learned this in the hard way!

The Ibrahim Nehme’s story was already on our radars since 2015 but has been suggested by one of our Swedish readers – Livia Podestà.

The Ibrahim’s cover portrait (ph. Diana Marrone) has been taken in a temporary wooden and social architecture sponsored by Swedish Institute for the Architecture Biennale in Venice, where me and him met for the interview.

To learn more of The Outpost http://magheroes.net/2-ibrahim-nehme/