Canal Diary, by Murillo

An audio novel for Portoallegro

Every one was quite confused. Presumably I was too, because my name is Murillo, that’s my Barge name. Boatmen change the name of their barges, often and without a specific reason.

On to the Mediterranean Sea, where my soul comes from, Nobody there changes the name of the boats, it’s seen as bad luck. And the Boats are not referred to as a “she” like here, but “things”, just as important but still things (Or ‘it’)… A boat should be called “it”. Just so.

Although nowadays I am known as Murillo, once upon a time I was Alexandra. My present soul, as I remember, comes from the 19th century (or even farther still), dressed in a soave and sophisticated glass and wood skin, borne out elegantly suited for the long afternoons of the Aintree races. From Murillo to Alexandra, or should I say, from Alexandra to Murillo, anyway I became, and always will be, a ‘she’.

So some may know that Barges are given names by their owners but every Barge also has a soul, it transmigrates over time, époque by époque, driver by driver. Souls never forget the stories they have witnessed. I have been so many things, from a pirate to a work-horse, a luxury cruiser. Would I like to begin another life? Of course, but first I have leave this place, here underneath. Knock, Knock. Please can you open me? I am here under your feet, under Bank Hall Wharf….

Oh, if I smell, I can recall the Rose’s Mush Prow, tasting now and forever of Flying Dutchman aromatic tobacco. Because Basil always had his pipe on day and night except when he was sleeping. Rose, felinely, hardly ever smelled unsavoury because Basil was clever. When they called him up for a new job, he always said yes to unloading Cotton here in Bank Hall, ready for it to be sent out with the carriages to factories and the cities beyond. Never and never did Basil take charges for the North, and never and never for southern Bank Hall as the night soil bound for Lancashire were loaded a few meter above at Sandhills.

But, whenever Basil arrived back in Bank Hall, you can be sure that he and Rose never returned empty handed. From Liverpool, many people came secretly at night to Vauxhall to ask for a passage. Bound for Wigan or Manchester, Rose’s nocturnal riders worked on piers or in warehouses and on those night’s Basil was busiest and the tea pot boiled restlessly all the while.

This was all before they changed my deck (or simply I dreamt of the change) this was before I became a ‘cruiser’. Yes, I remember, the tea was always on on those nights. My granny Carla’s ceramics, hanging upon the ceiling, was dark for the smoke! Around the plates, the nerofumo, sparkling by the pots got wider and wider and Basil wrote poems on it using his tobacco cutter as a pencil. He was noting his thoughts before they were gone. All were about Rose: “Oh, my Rose”.

In the first half of 19th century, here in Bank Hall, there was always a traffic jam of barges, especially around the wharf. Railways were becoming the issue, they were happen suddenly and rapidly. Passengers packet boats were being replaced by the trains. For goods, however, it was different, even in the years to come. We were not yet worried by the railway existence, we remained as we were, the railway was unmoving in our 4 mph world. Trains, as Butlers, were waiting – with their open mouths – gaping at us and our bulging stomachs of cargo. All the years I am alive – as you listen or read – I am still under your feet. I can tell that it was not the train that tried to kill the canal but mankind – guilty with the hurry of modern life.

Despite this, at the end of it, the canal was never completely stabbed to death, not me either and it effortless to dream of the canal exactly the way it was, a long time ago.

So today, September 18th, 1885, here in Bank Hall there is a marriage. The bride is the Bank Hall Hotel Grand-daughter, Nora, 23 years old and she will marry a Wigan landlord, who will take her with him immediately after the party tonight, here on the wharf.

The hotel is only a few steps away, back on Syren Street. The revellers come from here and there to dance, to sing and to sink a good half pint of Temperly Cider Brandy.

Me, Gifford and Mossdale are in attendance to transport the madams and the sirs. They are catching the trains up above and we are only a few minutes on the water before sitting them directly in their reserved coaches.

Gifford always runs on the Manchester canal but the owner was invited to the marriage and so came here in Bank Hall with his wife and nephew. This nephew was charged with looking after Gifford and bringing people to the train. Mossdale is the Bank Hall Hotel Barge. They use her to load Coal from Wigan, less expensive than the Coal changing hands in the warehouses beside Bank Hall.

Sometimes Mossdale strolls up to Leeds to buy cheese and cured pork for the winter. Tonight the warehouse is exceptionally empty and without workers it is used to store the boats moved from the wharf to accommodate the guests’ boats.

Farther, in the inner port there lies the bridal dowry, among them linen provisions and a beautiful wooden cupboard. When the couple leaves, they will take everything away and the bride and the groom (an important manager of the Canal Company), will travel with two fine narrow boats. These boats ‘Douglas’ and ‘Mersey’ were bought from a boat-lord, an independent loader who retired and left the canal life for a dry, country-cottage.

The new Mr and Mrs Dewmore will spend their honeymoon on the canal for fifteen days travelling toward Leeds. She would have preferred Edinburgh and London, a week in each, for the fashionable hats but Mr Dewmore, who had ordered four new hats for her for the marriage and for Aintree, would not agree on this. He intended to do business in Leeds, the enlargement of some Canal Company warehouses. So this honeymoon would be on the canal. A gramophone and a gallon of Somerset Cider Brandy, the same served at his wedding reception, would warm the duo on their long days of navigation to Leeds.

I never again saw ‘Douglas’ or ‘Mersey’. But I heard of Mr Dewmore, thanks to Mossdale who often goes to Wigan. Mr Dewmore used both of his boats after the marriage but had eventually sold ‘Mersey’. His wife had been unhappy traveling with him and the children in such cramped quarters and so Mr Dewmore was left alone most of the week days and needed only one narrow boat to accommodate himself.

I have a souvenir from the Mersey, a little shell garland put on with a subtle row. It ‘left’ thanks to a furious wind at the space between the warehouse and the Bank Hall Bridge. It was on her bow entrance and blew right onto my bow deck when the ‘Mersey’ was leaving, the last time I saw her. Nobody took the shells away, because the garland fell into the middle of my axis and is invisible to everyone except me. Sometimes when meeting another barges along the waterway the canal waves shake me and the shells touch each other. They smoothly speak Cling Clang and I recall the ‘Mersey’ with her deep blue and red sides.

The Bank Hall marriage party went on late into the September night, but nobody complained. The neighbours were used to the yard being used as a ballroom. Both the Bank Hall Hotel and a second one, named ‘The George’ a few meters down the road, used it regularly. It had long time been owned by the Canal Company, then by Parkes Brothers, who used it as Boat reparation and goods station to load and unload the moored Barges with cranes. After Parkes, it was owned by a couple of Irish- brothers, the Barry’s, who keep the yard, the warehouse and me, hidden in the tarmac-covered wharf. They would love to re-open the inner warehouse, restore it as a restaurant and hotel. I am sure that, if they succeed, I will finally be let out and return to sail on the canal!

When I was Alexandra, Bank Hall was spinning a different music and I was a cruiser, owned by one of the richest businessmen of all the navigation companies: I was his preferred Diamond. He sailed with me just for fun, happy with the sweet temperatures my glassy deck gave to him, even if in rain or snow. Then, on sunny days, he was proud to take off his business jacket and unwind on my deck. Mr. Andrew often summoned all his best friends for his Sunday morning trips, an unnamed dozen coming from the best North West Families. Together they reached Bank Hall from Aintree, where they stopped for the night. In the morning they were expected back at the harbour for meetings.

Often at Aintree, while they watched the races from the south bank of the Canal, Andrew and his friends let fly little letters for the surrounding Barges attached to long English roses. Jewelled white gloves collected the roses from water, just touching them with two fingers. The letters contained invitations to dances and charity teas in Liverpool. Often they were refused by the ladies but when they were accepted, evenings became parties with lights strewn all over the deck. I was, even more so, the most splendid amongst the races.

If being either Alexandra and Murillo, or even the souls I was before these, it is nothing more than the canal and even the sea which crowds my memories now.

The hard stones get softer by the covering mud and the sticky oil of the first engines. The seaweed and jellyfishes of the Mersey estuary push into the locks and stay with us, the barges. The decks and pontoons harshness never mitigated by the contact with the barges sides, the coaly black dust that landed on every surface seemingly to a paper covered by graphite.

From May to October, without stopping, the Narcissus and every kind of wild flower bloom around me and in the middle of it all, the birds come to nest.

All of this I will never forget, even if one day I will live free once again, to sail perhaps even for the North Sea. I will take some flowers with me to indulge, hoping their seeds will fall in between the wood on my decks and begin to grow. One day I will be able to bloom again for the coming season. A true piece of the Canal, then, will always live on.

—

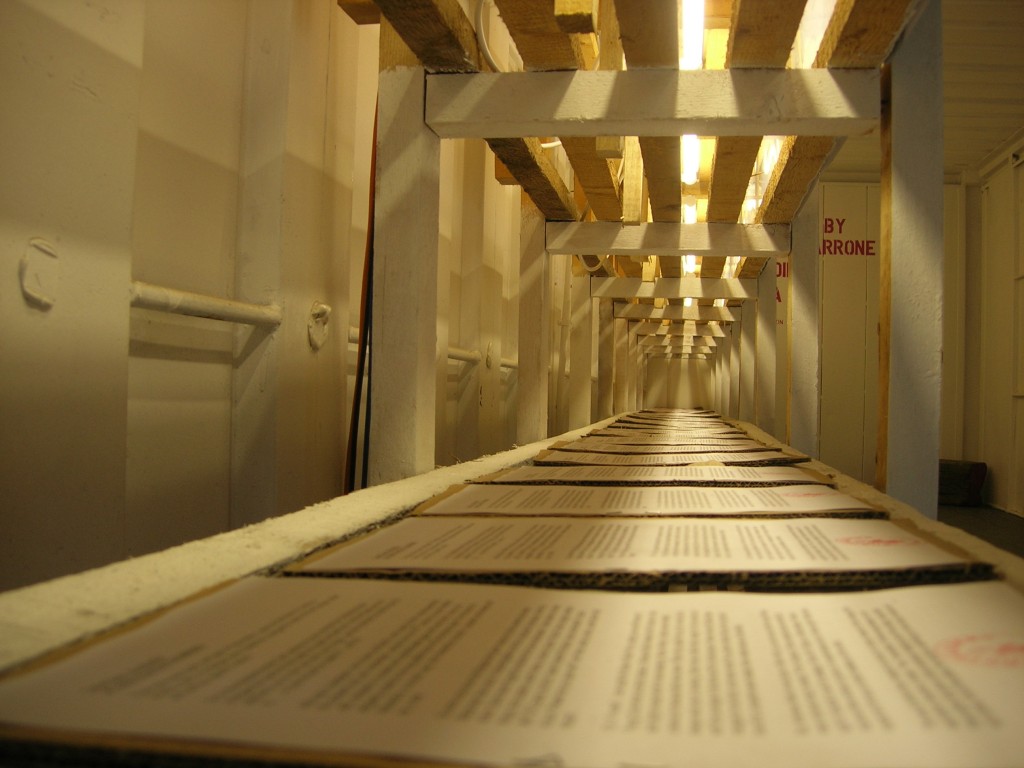

Canal Diary, by Murillo An audio novel for Portoallegro, has been created as part of a larger public art installation, Portoallegro, signed by Italian artist Danilo Capasso in Liverpool for the show and program Urbanism 2009, led by Liverpool Biennial to revitalize a canal area in the post-industrial fringe of the city.

The audio novel was set in one of the 3 containers hosting the basic facilities and amenities of the fictional Bank Hall Marina: a post office sending only postcards from the area, a coffee shop, a small cinema with a menu of movies including a feature film, Have you ever been down here before, signed by the artist, an art gallery.

Words, plot: Diana Marrone / Editing: Sacha Waldron / Sound design: Danilo Capasso

Acting and reading: Ms Lana H, Liverpool, September 2009

Total time audio-story: 20 minutes, suitable for children