Your story in few lines, without forgetting where did you met

I, Kathleen, was born in California, a middle child in a family of five. My mother was a good storyteller – you could tell she loved language. She loved the tributaries of family history and the descriptions of places. My father, a lawyer for farmers’ cooperatives in the Central Valley, felt strongly towards nature and the mountains – he was a fisherman when he could be. He took pictures of landscapes but preferred to leave the people out. As a child I loved any lonely place, or any imagination of a lonely place. There was a field near my house, a field that is now the home of an apartment complex, where I spent a lot of time. I dreamed about that field a lot. It turned out to be an Indian burial ground but they razed it and built anyway, making houses for professors. And in the imagination, there were the heaths and moors of any English novel from the 19th century, which I still find irresistible. I grew up in Silicon Valley before it was only wealthy. The weather is perfect and the people tend to be from somewhere else. I was educated in Catholic schools and developed an aptitude for gazing for a long time at one thing while sometimes thinking about another thing.

I, Young Suh, was born in Korea and my father was a military officer at the time. I went to college to study biology but I quickly found a student photography club that I immediately joined because I wanted to use the Nikon F3 that my father kept in a closet and never used, which eventually, they let me use. I got the camera, used it, and then I sold it to a pawn shop for drinking money. We got it out eventually, but then my friend bought if from me because again, I needed the money. After military service, I decided to quit my biology major and move to the United States, to go to school in photography with four other friends that I met at the photography club in college. I moved to New York and went to Pratt Institute where I met an incredible teacher, Phillip Perkis. I leaned to think of photography with a deeper meaning. After Pratt I went to the Museum School in Boston for a graduate program in which I first developed my interest in American landscape.

We met at Yaddo, an artists’ residency program in the woods of Saratoga Springs, New York, in the summer of 2011. It was a cloudy afternoon and Young was smoking. We spoke about landscape in art, and Katie looked at Young’s photos of the great California wildfires of 2008 – Young had gone in with the fire management crews who put the fires out to take pictures of the trees in smoke. One of the places he’d been was the Eastern Sierra Nevada, Mammoth Lakes, California. This is the more desolate and barren side of the famous mountain range that holds Yosemite and the blue splendors of Lake Tahoe. Katie had lived in that region for several years, teaching at a small school called Deep Springs where students operate a ranch and farm as they take classes. One photo took a view of the Jeffrey pines in the Owens River Valley through the smoke of the fires, with a far vista. The view, romantic but terrifying, was of a place Katie had been many times.

When we found each other, we spent a lot of time getting to know each other in silence, looking at work and at pictures. Katie had just come back from spending the summer in France. (Katie) maybe my English felt smaller because of that? As a foreigner, Young had always thought of poetry as a distant and mystical medium. Being able to speak with a poet in such intimacy was an amazing experience. (Young) Of course I fell in love with her immediately and her beautiful words, which she spoke every day to me.

What about Can We Live Here? and the recent UN Climate Conference in Paris: how did you combine your poetics with a glance over there?

We believe that art cannot fix the world. But it can help us survive. Human survival is the most beautiful subject.

When we think about climate change we don’t think about solving the problem. We think about surviving in a climate that is unpredictable, hard, or difficult. This is not because we are not interested in the problem. It is because we wish to look the problem in the face without illusions. The face of the problem is not simply the face of a mountain – it is a human face. We are living it.

The people of the Marshall Islands live on a disappearing landscape. The water levels are rising all around them. Their home shrinks. We recognize their struggle. We cannot hope to improve their lives – enough “improving” in the American fashion – we wish to, in our work, recognize their struggle. 2 degrees is not enough for them. If nothing is enough for them, who will save them then? It may be that the artists save something. Our job is a living memory – the landscapes we like feel like they are disappearing as well, as the zones we document are the high desert and the near Arctic. We want to contribute to a living memory of these places in a state of change.

There are all sorts of struggles caused by climate change. It is more than just melting glaciers. The human problems are becoming more apparent in migrations, poverty, natural disasters. The struggle is changing the way we live.

In survival mode, what we need is not just improvement of conditions but lots of storytelling. We are heartened that many already agree with us and find that storytelling has already risen among humans via social media far more than 2 degrees. We need a storytelling of living in a difficult world where things don’t always go the way we planned. This storytelling is the form of finding meaning when things are falling apart. We reside in beautiful California – a place where life often doesn’t appear to be falling apart, but where, on a closer look, it’s crumbling – through the gentrification of the cities, the diminishment of resources, ignoring the importance of the arts in favor of consumer technologies, through the contamination of the air in a place like Porter Ranch in 2016, in a state infrastructure that often feels on the edge of collapse, after a multiple year drought, watching the rain turn the hills green but flood the parched valleys – but we know how many are struggling in the state. California, a dream and a ruin, excites and challenges us.

We were on the radio. The host asked us what we were after in our work and we said, to show how to beautifully endure this struggle. The host said, but your pictures look peaceful and calm to me. Katie thought, but the people in the pictures feel stuck – the girl in the hot tub, the boy with the birthday cake standing in the middle of a wild desert landscape, a girl on a cell phone at an ice rink in December in Alaska. We want to show lives in a state of worry still able to find pleasure in the world, in human moments. We do not wish to make this uncomplicated. Anxiety can turn to joy in a moment, and turn back. The looks on the faces of the people we’ve taken pictures of know the water is rising and wish to go swimming anyway.

The Climate conference required global leaders of all kinds. We are most interested in the activists, the artists, the attendees who brought individual stories of difficulty and survival – who came with their private lives into a public space to tell their stories and advocate not just for change but for some acknowledgement of their presence on the planet.

If you can address an invitation to Mr or Mrs Obama to your exhibit or to one of the public events, talks or performances taking place during the show, which lines will you draft on the invitation?

Dear President and Mrs. Obama,

We want you to come to the gallery when it is quiet, when there is no event.

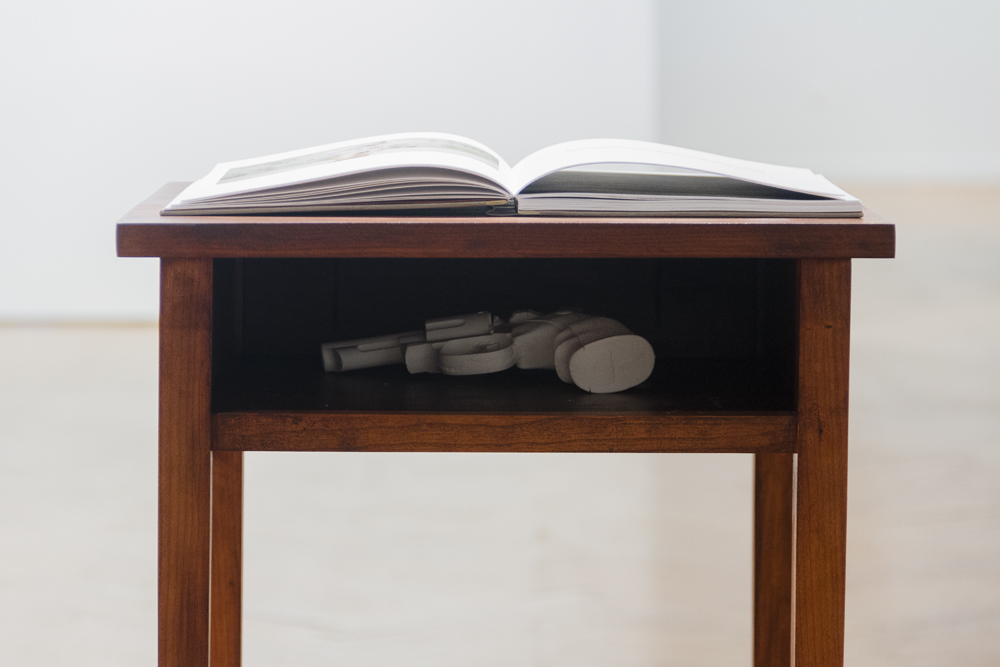

We invite to you sit and read about the entire world at a small desk exactly like the one in which the greatest American poet, Emily Dickinson, composed these lines:

My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun –

In Corners – till a Day

The Owner passed – identified –

And carried Me away –

We invite you to sit and read for a bit. We suspect at some point your hands will get restless and you might reach into the drawer of the desk and feel, inside, the shape of a something. We imagine you will wonder what this is, that you will move your chair out a little, and, distracted from your reading, look to see what you’ve touched. It is a gun – plaster, yes, a replica – but a loaded gun nonetheless.

We invite you to keep reading, to look at the beautiful landscapes and American portraits (many of the old and the young, many of people of color), knowing the gun is in the drawer. We have a sense this will not be a new sensation but a familiar recognition.

Finally, we invite you to meet our inspiration – the donkey. The most beloved and mistreated animal in the world, the donkey has much to teach us. We are not thinking of your democratic donkey, but of the donkeys of the whole globe, all 82 million of them, Indian and African and American donkeys, the donkeys in the Middle East who run drugs alone through the mountains with a tape recording of a human playing to keep them going. We think these donkeys outdo the symbol of your party. We are more interested in them. We invite you to look at the movies we’ve made about spending time with a donkey, about being interrupted, about wanting to do something beautiful and having it be changed – we wanted to make a donkey a perfect picnic, but the donkey sort of had other ideas.

We have a sense that you know something about wanting to do something beautiful in a difficult world, and having to deal with disappointment.

Come when it’s quiet and stay as long as you like. When you step into the gallery you step out of America and into the world.

Love Katie and Young

It is a dream, from the audience viewpoint, to see poems and photographic landscape together, given that one helps the other to be completed.

How did this collaborative project start? Was it a self originated idea or was it involving a curatorial spark? How will it be continued?

It started because we were imagining how we could live together. We had lived alone for a long time. We had wanted to live together for a long time. But when we began living together we had struggles. We spoke as a conversation with two halves, thinking in two different languages, Korean and English. We also thought in two different media, images and language. We needed to build something together in order to know how to live together.

We imagine ourselves on a road trip more than we imagine ourselves in a house. We met as travelers, really – at a residency where no one stays very long – and courted across the country, with Katie in Boston and Young in Davis, California. We spent a lot of time getting to know each other in remote places – Alaska, the High Mojave desert – making do with provisional orders, not the structure of a household. That structure was a mystery to us, something we weren’t sure we even wanted. But we began working together very soon after we met – we would give each other assignments to translate into the other’s medium, Katie would write a poem and give it to Young to film, or Young would give Katie a picture and she would write a poem about it. It was one way of finding out more about each other past conventional language.

Our first collaboration involved writing on the top of photographs – the tone of the work was rather elevated, ecstatic, panicked, like a scrawl on the mirror. A feeling of almost too much intimacy ghosted the work. But we liked working with a sequence and out of this emerged a form, a desire for a book, something to hold in the hands. We knew we wanted to make books. And we also started making film, a language that involves both text and image. In each case, the image, a kind of dream-recognition, began the work of art.

The curator Stephanie Hanor knew Young’s work and offered him a show – he told her about the collaborations and she got excited as well.

When two people imagine one life it is not always an easy path. We live differently. Young forgets about time easily. The world calls this “slow,” we think, but Young experiences it as simply real. Katie moves faster. What you see in the work is often an interest in speed – a desire to slow things down or speed them up. We made a set of slides and projected them from a moving truck onto the desert floor and filmed it as we drove. The images move like a film, but jumpy and rough. The slide projector we used, ancient technology, served our purposes very well. You can see the desert rushing underneath the images, many of people thinking or worrying. The people in the slides have been returned to the natural world. We wanted to honor them by taking them to desert, one of our favorite places, to see if they could slow down a bit there as photographic subjects. But doing the work was almost comically difficult! We needed friends of ours to drive the car. Katie projected the slides, and Young stood behind her with the camera filming to get the slide images in the middle of the camera’s lens. In the summer we worked with a bad truck and a rusty generator; in the winter our hands almost froze. These visual narratives are part of our film, Earthly Conversations and Slow Moving Things. The experience of making the film required Young’s patience and Katie’s fortitude.

From the whole to the intimate – from the very public to the very subjective: which scale do you find more suitable to speak about nature to young generations (and to your students)?

(Katie) I am interested in repeated experiences – anything that starts to take the shape, in time, of a ritual. Experiences can feel small or big to the human body. Many experiences in nature have the advantage of making us feel small in body. A humility governs this in feeling, but there is also a managing on the human scale – a retrieval of the very idea of a human scale, something being constantly questioned in a big world. I point my students towards small scales in language and experience. Emily Dickinson, or William Blake, see the natural world as symbolic and uncanny but also living. I ask my students to use all five senses. My favorite class is the one where we talk about a single haiku for an hour. Emily Dickinson wrote in a letter, “…I know the Butterfly – and the Lizard – and the Orchis – Are not those your Countrymen?”

(Young) I believe in experience rather than ideas. And experience is inherently intimate and individual. I want my students to experience before they know what it means.

(both) Young people are always attracted to big concepts and clear meanings. One clear meaning is the beginning of something new, from scratch. But nature doesn’t offer us this – it offers us a geological history, a cosmic time, a sense of the past that’s been marked and shaped by human endeavor. Whether nature is too much in human hands or not, it offers an understanding that redeems the individual as part of a greater whole. Our experiences in nature point out to us all that’s been created before our arrival on the planet.

Oakland: can you have two (one each) small, contemplative statements on the area hosting the museum in which you exhibit?

(Katie) The museum, a former ballroom, sits on a beautiful green campus in the middle of a neighborhood challenged by crime and poverty. It sits on a hill. But the museum is free. We heard a Black Panther, Elaine Brown, speak last year. She said, “Oakland is a radical city because it has a port that can be shut down.” Great community and great isolation can exist side by side in such a city. We thought of this when we arranged twelve replicas of Emily Dickinson’s tiny desk in a cross formation in the middle of the gallery – an opportunity for the community to sit together and read. Not a library, but a free room for the mind. Not easy to get to, but not impossible either.

(Young) The immediate image of Oakland I think of is Richard Misrach’s photographic work on the fires that destroyed over 3000 homes in 1991. Although all traces of the fire is gone, the city seems to have that memory of once being a ruin. Maybe all cities do.

Which is the book and the music with you now (and where the book lies in this moment)? Can you describe also the way you made the book that visitors can find in the show?

We guess what you are asking is what books and music we find companionable in the present moment, maybe since we have made books.

Young is completely consumed by Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels. He is excited about the power of personal narrative. He is at the end of the third book, and what he realizes is that the purpose of life is not creating a single meaning but the actual survival of life that consists of many parts that you are not in control of. Being able to fully live with intensity and earnestness is what her characters show. He also loves opera. For both these reasons he is excited that our interviewer is Italian – he has never visited Italy but longs to. Opera brings intensity into confrontation. The aesthetic experience should be pure intensity. The two best Verdi operas are Un ballo in maschera and La forza del destino, both stories of human destiny beyond one’s control.

Katie is reading writers who write about the North for a class she is teaching, paying special attention to indigenous women writers Joan Kane, dg nanouk okpik. Seamus Heaney’s wonderful book North with its preserved people found in the Irish bogs, Marina Tsvetaeva and Anna Akhmatova in translation. For pleasure, Mausoleum of Lovers, journals by Herve Guibert about love affairs he had and didn’t have, told in a diary and so told slowly, in real time. For music, one Catalan song in her head, Qualsevol nit pot sortir el sol by Sisa, Sweet Thames Flow Softly, the other song, and always Sandy Denny and Fairport Convention, anything folk when sadness has an edge, the song Tecumseh Valley by Townes Van Zandt. Songs where the music holds a feeling in color and detail, songs where the voice seems both to come from a real person and to be larger than any one person.

We designed the books together. It is hard to remember how it was done, and it was different in every case as we got to know the form. Young had the images and we would select groups and work with them. We wanted to follow a set of characters through the world.

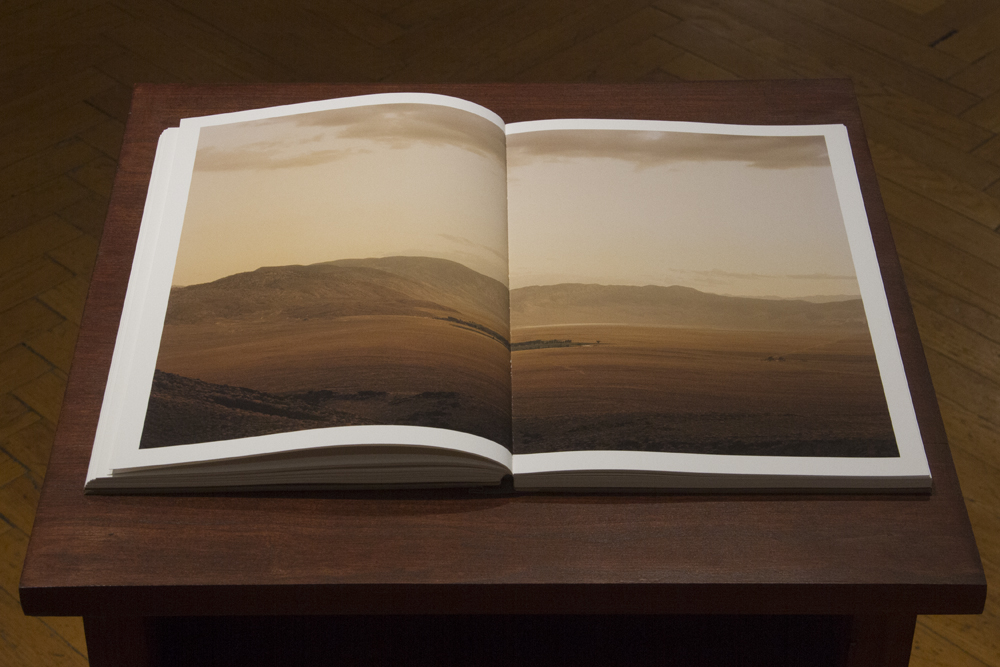

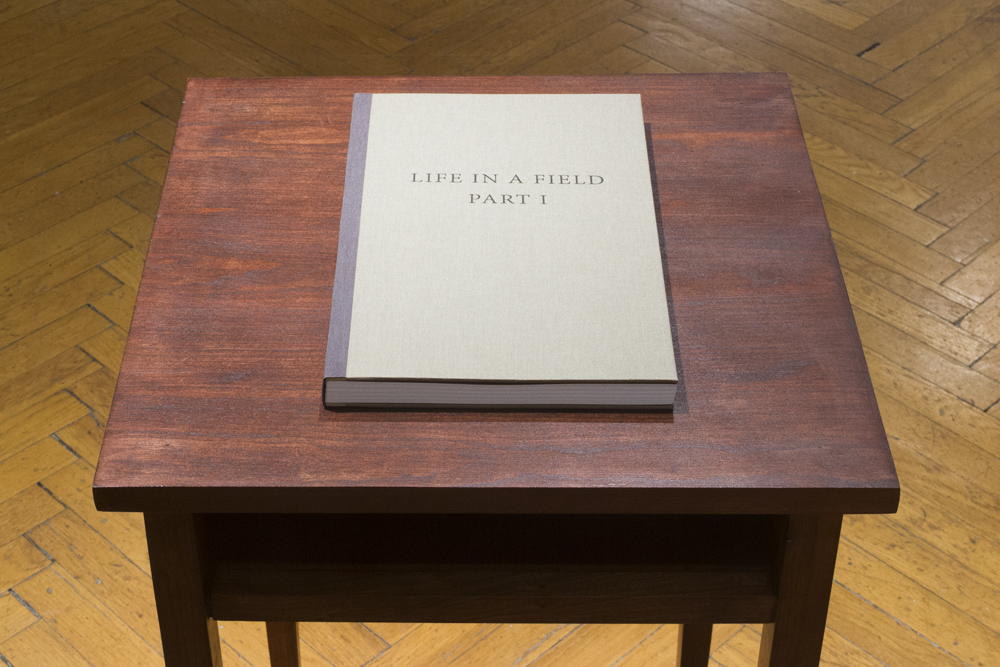

One set of books – four books – is called Life in a Field. It is a fable, a fairy tale without magic, about a girl who becomes friends with a donkey (you may know Au Hasard Balthazar by Robert Bresson – this is trying to be a comic version of that movie). Katie wrote it last spring and we put the book together this fall – the pictures don’t tell the story about a girl and a donkey, they tell a story about the larger world that story lives in.

The books were beautifully bound by Chris Martin, a binder who is also a poet, who has his own press in Colorado.

Which is the way you try to live slow, if you can or like, in a city like yours?

Young always lives slow. Katie finds this more challenging.

(Katie) Young lives slow by forgetting about time. He doesn’t manage time – he lets time manage him. He is happy to do one beautiful thing in a day. When I met him, he would ease into work for five or six hours and then start working in the middle of the afternoon. He still does this when he can. He lives slow by not asking always what things mean when he is in the middle of doing them. He loves looking at children, older people, people on the street – no one misses a look from him and his look is curious, outside time, like a poem, trying to be with the person for just a moment. He makes a cup of coffee so slowly, and it is the best cup. He goes for a walk, not a run. He doesn’t mind if he doesn’t get everything done- he forgives himself. The only thing Young doesn’t do slowly is eat.

(Young) Katie is always three steps ahead of me. Her brain works very fast and efficiently and I think she creates space for her slowness this way. For example she would clear out four hours in the morning to work on her poems before she starts a day, because poems cannot come out in a busy brain. I admire her being proactive of claiming her time. She is a very responsible person and tries to answer to the world all the time. She wouldn’t be able to make art without a strong commitment. The fastness has a desire to control slowness. Instead of being slow she might be trying to be fast enough to be slow.

What did you learn from life until now?

That life has its own plan, regardless of the person living it. That is not always so bad – that love can be a plan like that. Life is like family – sometimes you love it and sometimes it annoys the hell out of you. You have to honor what you can’t control and don’t know – you have to actually respect it.

Young Suh and Katie Peterson’s exhibition Can We Live Here? Stories from A Difficult World is on show until March 13, 2016 at Mills College Art Museum (Oakland, California).

For more information on the performance, screen and talks: mcam.mills.edu

To read more of Katie Peterson as poet and writer (apart the lines we publish on Slow Words for kind concession of the author) : http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/katie-peterson