Your story in a few lines, with some more hints on your childhood times

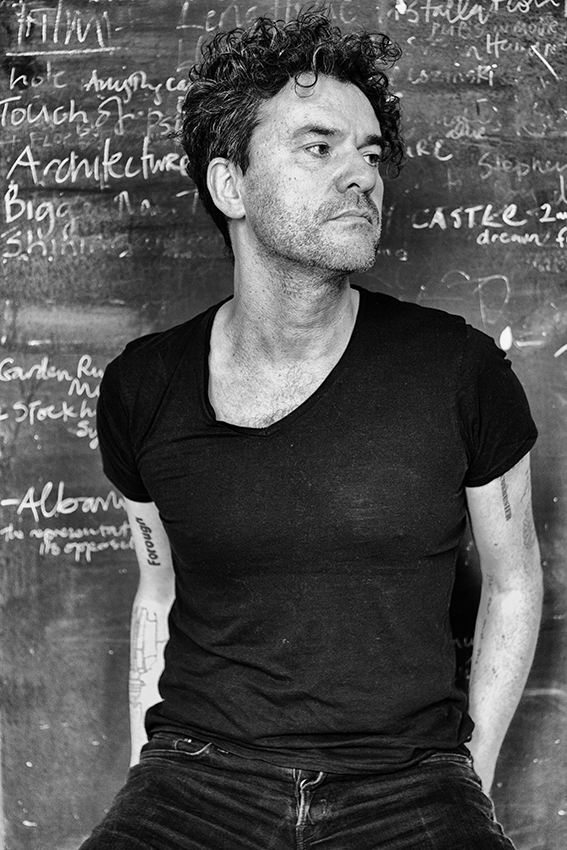

I am a Northern Irish, Edinburgh-living, slow-reading, brainy, happy, greying, wanderlusting, restless, vain, gentle filmmaker and writer who was brought up in Belfast during the Troubles, who studied film, art and philosophy, who has been with the same woman for three decades, whose film themes are walking, children, recovery and innovation, who has two books coming out in Italian (The Story of Film and The Story of Looking), who is completing a film on Orson Welles, who has climbed to the Hollywood sign naked, whose favourite artist is Tintoretto, who is an honorary professor of film, who is influenced by surrealism, who is easily bored, whose favourite writer is James Joyce, and whose favourite filmmaker is Imamura Shohei.

It’s better to tell you at the very start that I was making the route of ‘A Pilgrimage’ – the random movie-festival you organized and designed with Tilda Swinton in the Scottish more remote areas. Not when the festival was on, unfortunately, but just to discover the places you loved.

What was behind that idea and is there the opportunity to remake it?

I was brought up Catholic, so we had to do pilgrimages. As Tilda and I felt that cinema was our religion, we decided to show how much we are devoted to it by pulling a 37 tonne mobile cinema across bits of Scotland, to towns and villages which previously had no cinema. The idea was to do something visual, fun, accessible, devotional, memorable and innovative. No-one had done it before, so we decided to.

Which has been the spark behind your last director’s oeuvre?

The last film I made was Stockholm My Love, starring the great musician Neneh Cherry. It is a city film and tells the story of an architect (played by Neneh) who is recovering from an accident which was like an electric shock to her life. It is a musical of sorts – but a sad one – and is about how we recover from bad things. It was co-shot by the great cinematographer Christopher Doyle.

You’ve been among the jurors of the 2017 Venice Movie Festival (section Orizzonti), where we happened to meet during the marvelous screenings of this year selection.

Do you agree on the exceptional quality of original scenarios-scripts in this edition of Venice festival (in all the sections)?

I’ve never believed that the script is the heart of a film or, even, necessarily, it’s a starting point. We saw films with great screenplays – the Icelandic film Under the Tree, No Date No Signature from Iran, Oblivion Verses from Chile, Nico, the Algerian film Les Bienheureux, etc, but the most innovative film I saw had no script – it was Caniba.

More in general, which is the magic making you impatient to make a movie when it comes to words and stories: fiction, non-fiction or the new vague of a keen mix of the two? Which is the value of a ‘national culture’ in reading history and real life when you adapt or write a scenario?

The attraction of cinema is that it that it is magic and myth. It is surrogate life and time travel. I’ve made one fully fictional feature, and many films that you could call “poetic non-fiction”. It’s a deep human instinct to make things – things which resemble us but are abstracted in some way, or spiritualized, or beautified. Look at the wonders discovered in Knossos in Crete, or in Africa or in Meso-America. The most natural state of art is a hybrid of the real and the imagined.

If we look across the globe to films in many different countries, we can see national specifics – the moral disquisitions in Iranian art cinema, the nudity in Scandinavian cinema, the romantic laissez-faire in France, the pessimism in Russia, etc. But beyond these national characteristics there’s something universal in the language of cinema its, and in the rapture that it can provide for audiences. It is bigger than life, sublime and overwhelming, luminous like summer, expansive like a beach.

You as a reader: which places, which needs and which stories

I read lots of history and philosophy. I seldom read fiction, to be honest, unless it its densely literary..!

The book and the music with you now?

Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark; the new Mogwai album Every Country’s Sun.

Your favorite food and drink

I love lentils, mint, cumin, cloves, lemon. Very middle east.

Where do you see yourself in ten years?

I’m so happy and fulfilled that I’d like almost nothing to change. I’d like to continue to be creative, and to be healthy (my dad died when he was 56).

What did you learn from life until now?

Aim high. Dance. Be honest. Work hard. Go to funerals. Don’t take taxis. Don’t be a dick.

Mark Cousins is a director, filmmaker and screenwriter, film critic and the former director of the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

To learn more about his movies and his books: