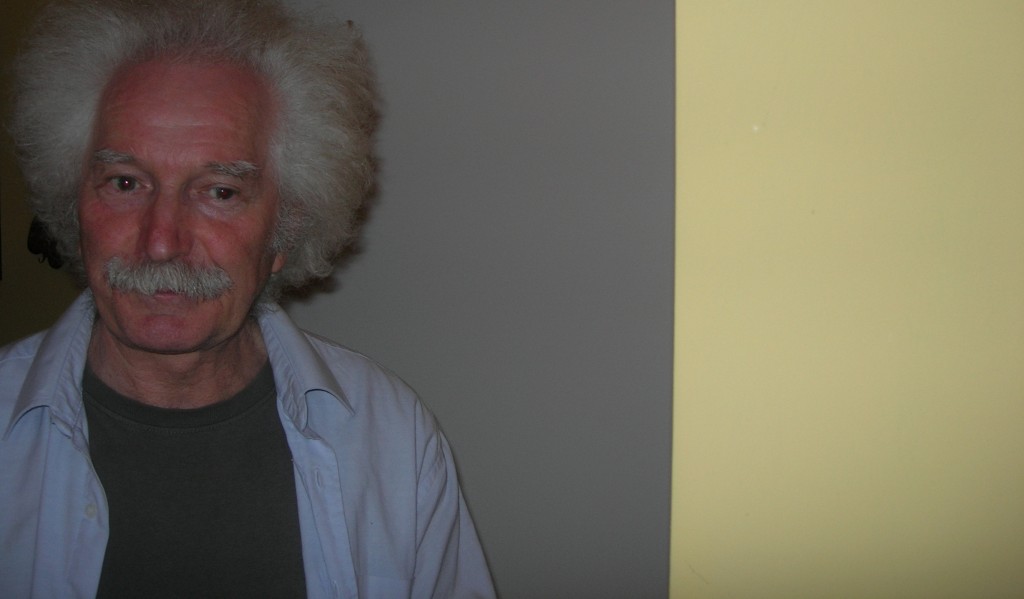

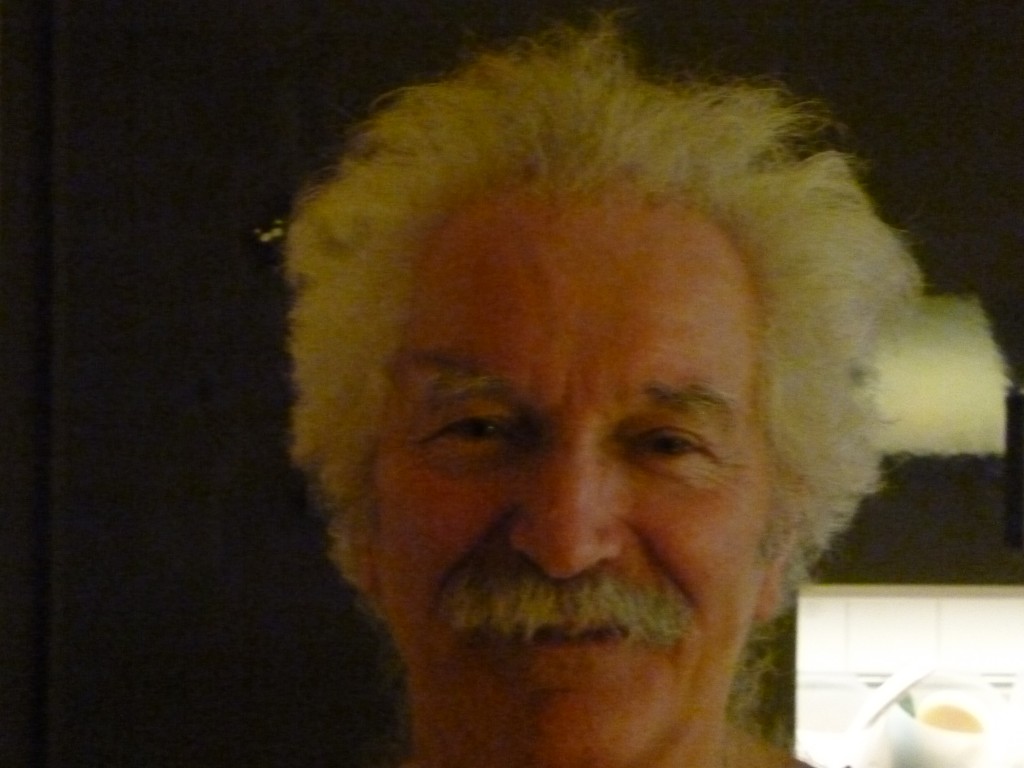

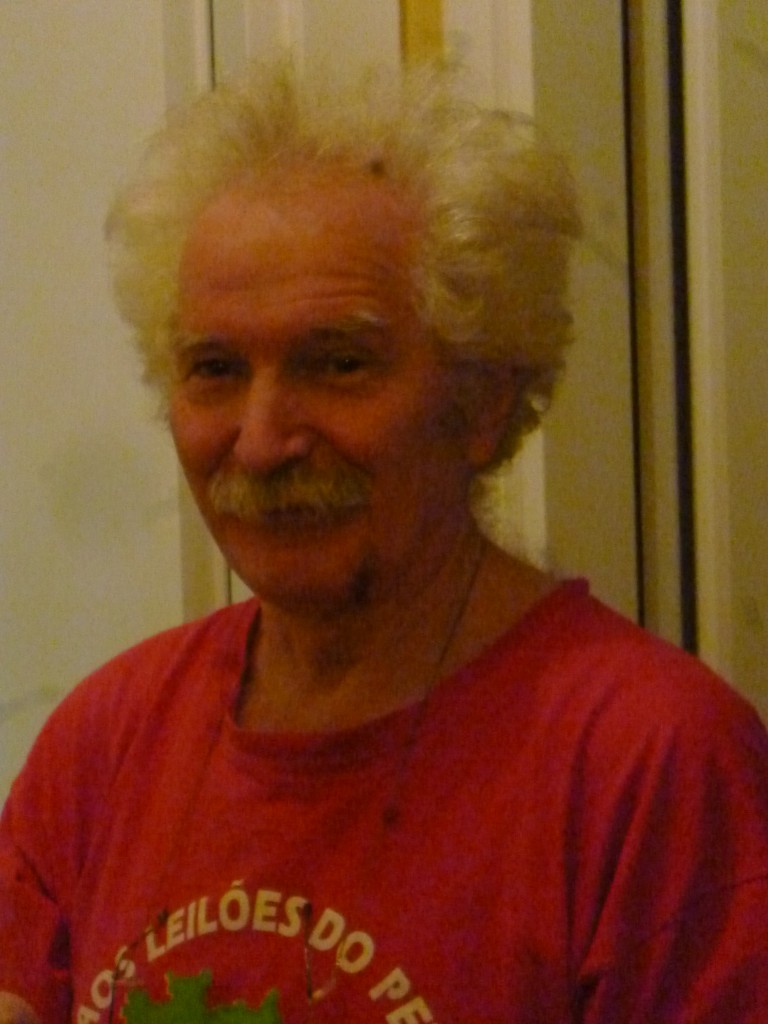

Renzo could be straight out of a photo of the early 1900s, when Montmartre and its painters began to be known around the world. The comic strip hair escaping from the beret, the mustache tickling the intelligent eyes – that’s the portrait of Renzo. His creative verve has always impressed me, and so I decided to find out a little more about where he came from.

Where do you live during the first years of your childhood?

I am from Verbania on Lake Maggiore. I was born right after the end of World War II, and for me the years of the late ’50s and early ’60s were years of conformist life made of home, church, and soccer. Then finally the slow, the parties, the movies, the boobs. The church is where you go to see the first movies, with the kisses – when there are kisses… Everyone wants action movies, and the church is the only place where they show movies and those are only action movies.

And school? How long do you stay at school in Verbania?

I studied to be a chemical consultant but then in 1964 I decide to go to university in Milan. The move to Milan is a real trauma: from a small world where everyone knows everyone to total anonymity. The relationships are not a given, natural, you have to look for them. I’m in a college, downtown, near Porta Romana. After almost a year of anonymity, I begin to orient myself, but everything remains less fluid than in Verbania. I only remember one great friendship, a college friend, who introduces me to a few people and shows me Milan. But it is not in Milan that I get laid, but in Verbania, where I meet a French girl, Nunù, with whom I then go to live in Milan for a couple of years (in Via Solferino, in a small attic apartment). Nunù stands for Annonciade, daughter of parents of Sicilian origin but born in Tunisia. Nunù is majoring in Italian literature doing a thesis on censored publications. I, by the way, am enjoying Milan – a place of continues partying and unexpected entertainment during the late 60s. For example, the famous protest of the Don Carlos at La Scala in December 1968: everybody is screaming, tomatoes are flying and I am there watching and enjoying the scene, when a Swiss passer-by asks ‘but what is happening?’ And one of the demonstrators promptly responds ‘Don’t worry, we’re protesting the Don Carlos.’ And the Swiss comments: ‘I did not know there was such passion for opera in Milan.’ These are stories that could happen only in those years.

And how then did you decide to leave for Paris (first trip – from 1970 to 1971)?

In Milan, I continue to do odd jobs and to study, but the military service is looming. To postpone it, I go to France to study, even though I am resigned to the fact that I have to do it – the civil service. But an unexpected joy saves me from military service: the moment of truth happens in Vercelli, where I go to find out where to start the service. I enter the room and they tell me ‘Giapparize: you’re not leaving’. What a thrill, a joy I had dreamed of a lot. The military has always made me anxious.

And so you finish your studies in Milan but leave right away for Paris (second trip – 1972-1977)?

Yes: I finish writing the thesis and defend it in the spring of 1972. And so I decide to go to Paris to Nunù’s, even if I’m going to muck around in the eighteenth (Montmartre). I ‘touch’ the center, I sniff the world, I meet weird people that I find very entertaining. People like the Customer: next to a flea market, I find a bar frequented by pensioners and workers, and one morning a guy with high boots enters, coat down to his feet, a scarf, in other words, a bell’omone, and orders – ‘un rouge!’ He receives the glass, takes it and empties it in the sink, before the astonished gaze of the host. The scene repeats itself: ‘un rouge!’ And the glass has the same fate as the one before. A situationist response to the rebellion, which apparently boils in Paris in those years. Another scene that I remember with pleasure is this one: I am sitting at a bar, and there’s a strange man with an alarm clock around his neck and some objects attached to him. I look at him, he smiles at me and says, ‘ça serait a rapport humain.’ I liked the idea – or you want to know me, or you see me as an idiot. The imperative remains to know, not to indulge or to be amazed at seeing the bizarre.

These are years of ‘strange stories’…

Ah, here’s another story from those days. I’m on the train, and a couple of ‘hippies’ enters, flowery shirts, and wide smiles. On the train, there is talk of this and that and the man, to celebrate the railway friendship, presents me with one of his wife’s tits – but she does not smile much… A gesture like an homage. The Parisian fooling around lasts three or four years: Nunù wins a major teaching competition and thanks to the times had been transferred to Charleville-Mézières and among her colleagues there is a friend, Remi, who I am still very close with. The visits to Paris happen for a chat, without doing a lot of things – to get to know the destinies. During those years I live as a flâneur, with tachycardia resulting from indecision. On the occasion of the return to Verbania for my mother’s funeral in 1977, I am offered a job for teaching science in a high school, then at the institution for surveyors. These too are years of fun. I recently met a young man who still remembers some of my sentences: ‘Young people have only one duty: reading and screwing.’ I also remember another of my former students, and her return home after school. She’s distressed and crying, and crying says to her parents: ‘I do not want to live like you, I want to live like Giapparize!’ Really years of absolute fun, even though I decide to move to Milan in 1980 because Verbania is beginning to see me a little too much as a character. Since then I stay between Milan and Abbiategrasso, to then spend the rest of my career at an artistic high school in Milan.

And do you have any other memories of other students?

You know, every now and then I meet someone on the street. A few years ago I met a former Bulgarian student of mine – clearly homosexual already as a young person, likeable, an authority on so many songs in Milanese dialect – he hugs me, and reminds me of another one of my mottos at the time: ‘The ass is always smarter than the head because he knows what he’s doing! Consult the ass, and then answer.’

What did society and Milan do for you?

I owe everything to society and to Milan, school, sanity, the heaven I have experienced so far.

And what have you given to society?

Well, I think I have given it a good mood. And plenty of it.

What is your favorite dish?

There isn’t only one dish, in general I like the simple things – bread and olive oil, a green sauce, bruschetta. The simpler they are, the more comfort I feel, even a slice of salami or mortadella…

What is your favorite drink?

Red wine, organic (for the joy of militancy), it shouldn’t be acidic, it must be round, and must persist a bit on the palate and have a nice scent of cellar, of aging.

What music do you listen to?

Usually, Jazz. Discovered through a friend from Verbania, and then the sound of jazz stayed in my heart. Then I bought a trumpet with the idea of playing it a bit. The book of predilection is Chekhov – his short stories. Now I’m reading – in fact, re-reading – Seneca’s ‘Letters to Lucillo’, and ‘Dead Souls’ by Gogol.

What is your best talent or a quality you recognize having?

I think I’m capable of materializing the absurd, one of my generally much appreciated qualities. And I can enact perseverance, leaving violence behind.

(translation: Benedicta Bertau)